“Spiraling Downward: America In “Days Of Heaven,” “In The Valley Of Elah,” And “No Country For Old Men”*

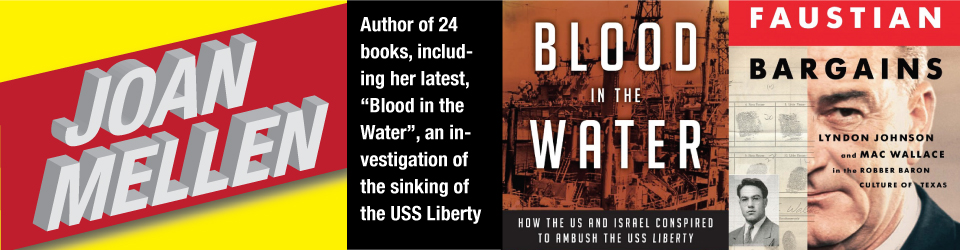

BY JOAN MELLEN

On the day the first European settler disembarked on this continent and noticed the inconvenient truth that there were people already here, the American character was hatched. In “Days Of Heaven” (1978), newly restored in a director-approved digital transfer in the Criterion Collection, Terence Malick picked up the chronicle of America’s political and cultural identity in the early years of the twentieth century. For Malick, the returns were already in.

“Days Of Heaven” unfolds in 1916 and 1917. “No Country For Old Men” (2007), set in 1980, in an explicitly post-Vietnam aftermath, assesses the damage sixty-four years after the events in Malick’s film. Following Cormac McCarthy’s courageous novel closely, the Coen brothers depict the endgame of a society so at war with itself that there is scant respite, even for the one brief lyrical moment in time that Malick depicts. It is the endgame of America’s final fall from grace.

While the drive for personal gain in the early years of the republic is depicted in “Days Of Heaven,” its global consequences emerge only in the Coen film. The toll of America’s ruthless pursuit of advantage is exposed with even greater explicitness and horror in Paul Haggis’s underrated “In The Valley Of Elah” (2007). Both of these more recent films were shot brilliantly by Roger Deakins, and both take as their implied mission to awaken a political bewildered and lethargic audience.

Thematically, “In The Valley Of Elah” might be viewed as a coda to “No Country For Old Men.” Both convey the same idea: that America’s young men, drilled and educated so as to fight America’s expansionist wars, have been morally damaged simultaneously with the deterioration of the national ethos. Although these films view the war veterans at their center as victims no less than executioners, this theme has not generally been noticed by critics.

There is, however, ample reason that “In The Valley Of Elah,” as well as later films chronicling the psychological damage of the Iraq war like “Rendition”(2007), “Redacted”(2007), and “Stop Loss” (2008) have not done well at the box office. Their message is devastating. The greed for personal gain, land and empire, through its foreign wars and adventures have, from the mid-twentieth century on, stripped from America any claim to decency and uprightness as a culture of democracy. The highly trained soldiers and former soldiers in “In The Valley Of Elah” and “No Country For Old Men,” formidably skilled in violence and tactics for survival under unspeakable conditions, returned home as deformed human beings, tormented by their experience and a danger to others and to themselves. This harrowing conjunction of professionalism at war and personal brutalization may be read as a metaphor for the entropy of contemporary America. All three films contribute significantly to the political discourse of these times with Iraq appearing in Paul Haggis’s film as the natural consequence of Vietnam.

Cormac McCarthy’s uncompromising novel upon which the Coen brothers based their film references Vietnam specifically a number of times. With a nod to the exigencies of commercial cinema, the Coens’ film does so only twice. First, Lieutenant Colonel Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson) asks Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), “Were you in Nam?”

“Yeah, I was in Nam,” Moss says. At this, Wells removes his hat in homage, adding, “So was I.” Later at the Mexican border Moss gains re-entry to the U.S. only after the guard learns, to his satisfaction, that Moss served two tours in Vietnam.

Yet it is clear that the film’s ruthless killer, a tool of the drug lords, Anton Chigurh (Javier Bardem), no less than Moss and Wells, honed his murderous skills, along with his uncanny ability to tend to his own wounds, in the jungles of Southeast Asia. Three key characters in “No Country For Old Men” are returned Vietnam veterans. Moss enters the film shooting pointlessly at a herd of antelope in the absence of human targets; addicted to killing, like the soldiers on leave in Texas in “Stop Loss,” he reveals by his action what McCarthy tells us in the novel: he had been a sniper in Vietnam.

“Vietnam was the icing on the cake,” McCarthy writes, referring to America’s long bloody history beginning with its disregard of the humanity of its original inhabitants. The Coens omit this line, along with Deputy Wendell’s remark as he and Sheriff Bell (Tommy Lee Jones) survey the bloody death scene of Mexicans in their dope-laden trucks: “It must of sounded like Vietnam out here.”

“Vietnam,” Sheriff Bell repeats somberly, as if the word itself expressed the depths of bloody suffering.

The once independent Republic of Texas, settled as it was by outlaws, forgers and worse, is the setting of several of these films: “Days Of Heaven,” “No Country For Old Men” and “Stop Loss,” as if that state with its obsession with high school football, and guns of every shape and variety, were the perfect analogue for an America at loose in the world. Since the discovery of oil at Spindletop in 1901, Texas has been a barometer of America’s moral direction, a point that Malick, son of a Texas oil executive, had to have appreciated. Like the Coens’ first brilliant western-noir, “Blood Simple (1984), “No Country For Old Men” takes place in Texas. Haggis locates his film a stone’s throw away, in New Mexico.

There are no heroes in these films as their participation in aspects of genre might demand. The “Farmer” (Sam Shepard) in “Days Of Heaven” attempts to construct his happiness on another man’s misery and ill fortune. Sheriff Bell perceives that far from being a “hero,” he is a moral anachronism, and defenseless against a new breed of criminal who respects no boundaries. Hank Deerfield in “In The Valley Of Elah,” played, again, by Tommy Lee Jones, in what seems like a latter-day incarnation of Sheriff Bell, discovers the same truth; he searches for the truth of what happened to his son through cell phones, computers and video enhancements (a technique used in “Redacted” and “Stop Loss” as well) only to discover that the new technology doesn’t do anyone any good.

A monstrous distortion of the human has arrived, making films like “No Country For Old Men” and “In The Valley of Elah” seem more like science fiction than like westerns. Questioned about his character in an interview for “The Los Angeles Times,” Bardem said, “He belongs to somewhere else. I’m not saying from outer space, but [he] belongs mentally to someplace else.”

Sheriff Bell in “No Country For Old Men” and Hank Deerfield are defeated by men who are hybrids, grotesque mutations spawned by America’s wars of empire. Among these morally mutilated beings is Hank’s own son, who had been a Bible-reading boy of conventional uprightness before he was shipped to Iraq. When Mike (Jonathan Tucker) telephoned home and pleaded, “Dad, get me out of here!” Hank, a Vietnam veteran, urged him to carry on. That call, repeated several times in flashback, expresses cinematically Hank’s sense of his own guilt, expressed in repeated involuntary memories of a pivotal moment when he did the wrong thing.

A type of man, a being Cormac McCarthy calls a “new kind,” a reflexive, yet entirely lucid, sadist, has been let loose on the American landscape. The man left standing at the close of “No Country For Old Men” is the stone-cold killer Chigurh, played with unerring exactitude in an Academy-award winning performance by Bardem, who is barely recognizable as the actor who played, with similar virtuosity, the gay Cuban poet in Julian Schnabel’s “Before Night Falls” (2000) and the bedridden paralyzed figure in Alejandro Amenabar’s “The Sea Inside” (2004).

Unrelenting, unflinching, ministering with intense concentration to wounds that would have defeated most men, Chigurh is a paragon of military discipline, not least because he has been trained to extinguish all compassion. In its place is a chilling rationality and rigor, an absolute commitment to self-assigned objectives. In conveying all this, Bardem adds to his conception of Chigurh a slight air of boredom and impatience, the sole traces of humanity remaining to him. Only vestigially human, Chigurh is likened in McCarthy’s novel to the “bubonic plague,” even as, further linking these films, a plague of locusts descends on the farm in “Days Of Heaven,” a catastrophe redolent of poetic justice.

With the irony of Moss’s mistaking his name for the word “sugar,” but sounding more like “chigger,” a parasitic larva of the harvest mite, Chigurh is a direct descendant of Joseph Conrad’s Kurtz. Once the emissary of “pity, science and progress,” as Conrad put it, Kurtz ends up a murderous madman, answerable to no one. He decorated his Congo encampment with the shrunken heads of his victims, and only, at the moment of his death, could he pass judgment on the entire imperialist enterprise, of which he was a part: “The horror, the horror.”

Chigurh murders with a high-tech air gun, like those used in abattoirs to dispatch cattle. The motif plays again in “In The Valley Of Elah,” where Specialist Bonner (Jake McLaughlin), a butcher by trade before he joined up to fight in Iraq, cuts the freshly-killed corpse of Hank Deerfield’s son Mike into pieces, then tosses his body parts into an open field to be feasted on by passing wildlife. Mike’s buddies are Kurtz’s descendants no less, although they do not reach Chigurh’s level of evil. Bonner hangs himself, leaving Mike’s baby-faced executioner to live to tell the tale.

These men, having returned from Vietnam and from Iraq, have grown, in varying degrees, into instinctual killers. The soldiers and former soldiers in “No Country For Old Men” and “In The Valley Of Elah” surpass Kurtz in one respect: they have brought their atrocities home. Both films depict a precipitous decline in the moral tenor of American society where the safety of its citizens has become, as never before, a virtual anachronism, and, as “Redacted” and “In The Valley Of Elah” make clear, the enemy is not Islamic terrorists. The enemy has become ourselves, our own young warriors.

A SICKENED SOCIAL ORDER

“Days Of Heaven” dates America’s deterioration earlier, from the moment a rapacious industrialism enveloped America and the class divide widened vastly. A sepia montage of ragged immigrants accompanies the opening credits, while the first sequence is set in a Chicago factory under deafening noise. Bill (Richard Gere), provoked, murders the steel-mill foreman accidentally and must flee into the already pitiless American heartland. Bill will kill twice, both times in self-defense, even as Chigurh might also be seen as a victim of the task he was enlisted to undertake.

Bill escapes on a freight train of immigrants traveling west and selling their labor to farmers. He is accompanied by his fourteen-year-old sister Linda (Linda Manz, a non-professional actor), and his girlfriend Abby (Brooke Adams). In Texas, they encounter conditions as barbaric as those they faced in the filthy urban ghettos of Chicago.

In the West, silence prevails so that Malick produces what amounts to a quasi-silent film, drawing his themes from image alone.

The Farmer for whom Bill, Linda and Abby work is mostly silent. He is a single man whose name is his function, the accumulation of personal wealth and property. Innocent Linda is enlisted by Malick for voice-over narration, in contrast to the Coens’ (and McCarthy) choosing the seasoned Sheriff Bell to tell the story. In her naivete, Linda can be shocked by the inequities between rich and poor, and the absence of fairness:

“Some people need more than they got, others got more than they need.”

“You’re on this earth only once and in my opinion, as long as you’re around, you should have it nice.”

“Whoever was sitting in the chair when he [the Farmer] came around, they’d get up and give it to him.”

“You didn’t work, they’d ship you right out of there. They didn’t need you. They could always get somebody else.”

With references to the Book of Revelations, Malick suggests that class society awaits a final, irrevocable judgment, one he foreshadows as the locusts descend on the farm. It is fitting that the aberrant high angle shot introducing the plague contains a scene of Linda encountering the first locusts in the farm kitchen.

Linda is not, however, totally reliable. Of the Farmer, she concludes, “there was no harm in him,” although there is certainly harm in the social relationships depicted here. She insists that her brother and Abby are “kind-hearted,” although they leave devastation in their wake.

Finally, the images tell the story. The walnut-carved Victorian-style chair is upholstered in rose brocade. Placed incongruously out on the open prairie, it is as anomalous an object as the distorted social relations between the characters in the film. Medical care is reserved for the Farmer; the hired hands must steal medicine, and, like the livestock, live outside in the open.

Slow dissolves punctuate this film as one shot slowly merges into another. Malick reveals how for people like Bill, Linda and Abby one day is exactly like the next. Bill had promised Abby that “things aren’t always going to be this way,” while Malick renders these words ironic by inserting a clip from Chaplin’s “The Immigrant” (1917. The immigrants toiling in the Farmer’s fields until, their labor done, they are shipped off, look forward to a future inhabited by Charlie Chaplin’s tramp.

The sublime cinematographer Nestor Almendros’s shots of nature suggest nostalgia toward the unrealized possibilities of an America with bounty for all. Yet, already by the early twentieth century, the gulf between rich and poor had widened exponentially. Malick expresses this idea through imagery of the grotesque, beginning with the ornate three-story Victorian mansion rising out of the prairie. Reconstructing Edward Hooper’s “House By The Railroad” (1925), the imagery also suggests the despair of the Andrew Wyeth painting, “Christina’s World” (1948).

The verticality of the house where the Farmer alone enjoys the creature comforts of civilization simulates a knife stuck into the peaceful horizontal golden fields of wheat. In one shot, Almendros interrupts an otherwise persistently moving pan to pause on the aberrant mansion rising out of the earth. In another, the dissolve is so retarded that the mansion, a symbol of inequality, appears twice in the same frame. Other shots offer similar rebukes to class society. In extreme close-up, the locusts, a judgment on the already inexorable decline of America, chew obliviously on the harvest (some were glued to the stalks of wheat). Their mandibles moving, unstoppable, they foretell the bitter future of a social system that reserves its benefits and its comforts for the few.

Malick and Almendros decided that no blue sky should appear in “Days Of Heaven,” the better to suggest the moral darkness. Many shots are backlit, while fields of four-foot-tall glowing wheat symbolize the wealth concentrated in the hands of one man. The immigrant drones are profiled like insects, silhouettes against the horizon, deprived of the luxury of individuality. Darkened silhouettes, their features are not articulated. It was Almendros’s method to add no supplemental light to the exteriors.

Malick’s signature shot in this film is the low angle looking up, an angle enjoyed by all the characters, the better to express the director’s point of view, his egalitarian spirit that will not privilege the rich. In one scene, Bill and Will sit side by side, doubles. With Malick cutting from one in close-up to the other, keeping them apart, as the class hierarchy so ordained, Bill confides that one day he woke up and realized that he would never “make a score.” They are two young dark-haired men, one with more money than he can ever hope to spend, the other with no prospects at all, and each murderous when crossed. One could easily have been the other. As their characters merge, both men being lovers of Abby, the slow dissolve renders them equal.

In a shot that arrives late in the film, a train bearing President Woodrow Wilson steams through the Farmer’s land without stopping: conventional politics promise no relief. With metaphoric flamboyance, Malick then adds a conflagration to the climax of the film, as if only a complete purging will redeem the sickened social order; the fire culminates in Bill’s murder of the Farmer with a screwdriver.

The fire expresses the film’s moral judgment. The Farmer had no right to love Abby, and no right to build his happiness on another man’s misery, and he pays for it. At the end, mindlessly joyful recruits board a train for the killing fields of World War I, Abby among them, her freedom as illusory as the Farmer’s.

Linda, strolling aimlessly down a railroad track to nowhere, hopes things will “work out” for her friend, a girl she met on the farm. Of her own prospects, she says nothing because she knows she has none. It is now 1917, year of the Bolshevik Revolution, reinforcing Malick’s unsentimental invocation of the hindsight of history and what might have been.

WITHOUT VANITY OR MOTIVE

“No Country For Old Men” is set on a flatter landscape of West Texas desolation where nature can no longer be enlisted even ironically as a metaphor of transcendence. The opening montage of shots devoid of human habitation emerges under a white sky, no blue here either, as Sheriff Ed Tom Bell offers his first monologue in voiceover. The level of urgency has risen, even as the Coens, like Malick, depict a society devoid of safety, tranquility or solace.

In place of Malick’s low-angle shots, the Coens offer rhythmically the extreme high overhead angle. They look down on Chigurh killing a deputy, or cleaning his leg wound in a bathtub, or Moss entering a gun store. The Coens distance themselves from events that no one has any hope of mediating. The high angle creates an abiding sense that the film itself is frightened of Chigurh. McCarthy in his novel pauses for moments of explanation: “fortunes been accumulated out there that they don’t nobody even know about. What do we think is goin to come of that money. Money that can buy whole countries.” The Coens rely on the image.

Motive in this America, as Malick had predicted, is a luxury and an irrelevance. Moss takes the $2 million of Mexican drug money he comes upon by chance without ever articulating why, even as he knows the danger he faces. “Things happen, I can’t take them back,” says Moss, a descendant of Robert Altman’s ill-fated entrepreneur, John McCabe (Warren Beatty) in “McCabe and Mrs. Miller” (1971). McCabe seems to be doing well in his business only to fall into the death machinery of the monopoly-minded Harrison-Shaughnessy mining company. Their enforcer Butler (Hugh Millais) is a direct ancestor of Chigurh. Neither is authorized to “make deals,” only to kill.

Chigurh is a more horrific figure than the seven foot tall Butler. He murders not for greed or personal gain, or because he has any loyalty to the greedy oil entrepreneurs operating out of Houston skyscrapers, but because, as he says in his most revealing line, a throwaway, “That’s the way it is.” His semi-Buster Brown/Prince Valiant haircut, neatly tucked under, and adding an asexual aspect to his appearance, bespeaks a man without vanity. He is a man with no human connections, nor does he experience their absence. The odd haircut was, the Coens have revealed, modeled on an old photograph of a man at a border whorehouse. Chigurh expects nothing for himself from anyone, but, as the sheriff concludes, it would be too easy to call him “insane.” It would render Chigurh a special case, implying that his elimination could restore society to its natural order, and it is too late for that.

Because the verbal is rarely reliable for either Malick or the Coens, the last words Moss speaks in person to his wife Carla Jean (Kelly Macdonald) are an ironic reprise of General Douglas MacArthur, a man of another era and one who made good on his promise. “I shall return,” Moss smiles. He will not. Moss is murdered off screen, an event dramatized by a rare fade within the scene. This fade arrives without warning, and is the film’s symbolic requiem for ordinary young men like Moss, a welder by trade, a descendant of Malick’s Bill, and doomed by the damage inflicted on the participants of America’s wars of empire.

The Coens leave out McCarthy’s scene of Moss’s death, and its context. Moss has picked up a young female hitchhiker and he dies when a Mexican thug holds a gun to this girl’s head, demanding that if Moss does not drop his gun, he will shoot her. Moss complies. The Mexican then shoots them both. McCarthy underlines the difference between the two men: Chigurh would not have cared, and so would have survived. Moss calls her “Little Sister.”

McCarthy and the Coens chronicle a trajectory of dehumanization. Moss has been damaged by Vietnam, but, affectionate and loyal to his wife, Carla Jean, he is capable of love. Colonel Wells, sent by the drug people to retrieve the money Moss has taken, represents a further step to human degeneration. Having served as a colonel in Vietnam, and no mean killer himself, Wells remarks to Moss that Chigurh is “not like you. He’s not even like me.” It is certainly true that Chigurh would never have risked his life to bring a dying Mexican a jug of water, as Moss does.

The least damaged of the men in this film is Sheriff Bell, whose behavior during World War II was not wholly honorable…at one point he abandoned his men to save his own life. Yet Bell is capable of a loyal and lasting relationship with his wife, Loretta (Tess Harper), of genuine love and sensuality (the Coens in a misstep don’t include the moment when Loretta bites his ear, McCarthy’s suggestion that their sexuality remains intact despite their advancing years). Just as Malick relied on a pattern, the love of two men for one woman and the turmoil resulting inevitably from that struggle, the Coens present a downward spiral of human character. They move from the sheriff, a good if flawed man, to Moss and Wells, who are transitional figures, and then on to irredeemable Chigurh. The suggestion is that, finally, the differences between Moss and Chigurh are transitory.

What defines the “new kind,” the new America, and the evil that Sheriff Bell “doesn’t understand,” are the similarities, not the differences between Moss and Chigurh. Both men have been newly fashioned out of the crucible of imperial war, and both have absorbed the lessons crucial to their survival. Both reveal a professional knowledge of all types of guns, although Moss never kills anyone in the film, but for a gratuitous pit bull who didn’t appear in McCarthy’s novel.

“Hold still please, sir,” Chigurh urges his second victim.

”You hold still,” Moss whispers to a distant antelope as he takes aim.

Later Chigurh, out of the same reflexive impulse to kill anything that moves, shoots at a random innocent black bird (he misses). Both veterans have become involved in the drug trade. In an understated moment, as Moss alights at a motel, with the drug money in tow, he phones a Mexican named “Roberto,” only to reach an answering machine. No explanation from the Coens is forthcoming. “Roberto” never appears in the film.

Covered with blood, Chigurh and Moss, as they must have done in the jungles of Southeast Asia, keep going. Both move through the film expressionless, and Moss shows no reaction when he opens the Mexicans’ black briefcase and sees that it is filled with hundred dollar bills. Shot, they tend to their own wounds, neither expecting help. Both buy clothing from bewildered passers-by using hundred-dollar bills from the drug money.

They are connected by sound bridges; they are connected over cuts. We believe we are in a taxicab with Moss only for Chigurh to be behind the wheel of a truck. One shot at the Eagle Pass Hotel, near the Mexican border, is from so low an angle that we see only boots. Temporarily the spectator is confused: are we inside Moss’s hotel room, or outside in the corridor with Chigurh?

As for Bell, whose less-than-heroic wartime experiences are recounted only in McCarthy’s novel, he drinks from the same bottle of milk still sweating from Chigurh’s having only moments earlier removed it from the refrigerator in Moss’s abandoned trailer. Sheriff Bell cannot imagine that Chigurh, having captured the drug money, with Moss and Wells both dead, would go back and kill Carla Jean simply because he had vowed to do so. “We’re looking at something we really ain’t even seen before,” Bells says in the novel, echoing Marlow in “Heart of Darkness”: “I had to deal with a being to whom I could not appeal in the name of anything high or low.”

“Who are these people?” the sheriff asks, rhetorically, while the Coens dramatize the reply: they are ordinary Americans, playing out at home the atrocities of Vietnam where you shot without seeing the enemy, where you shot compulsively into the darkness.

“OVERMATCHED”

In “In The Valley Of Elah,” Hank Deerfield, likewise, cannot at first comprehend the psychological and moral deformity that has been visited on those who have been fighting America’s wars. “You do not fight beside a man and do something like that to him,” Hank says, with dramatic irony, referring to the possibility that his war comrades butchered his son. Haggis dramatizes his Dostoevskyian premise without qualification: if you can thrust your hand into a detainee’s open wound to make him scream, as Mike Deerfield did in Iraq, you can do anything, as Mike’s own buddies do when, over a petty spat they stab him repeatedly, then carve up his body with a butcher knife.

Victim though he may be, Mike too was corrupted in Iraq. In a scene from the shooting script that did not make the final cut, Mike visits a girlfriend who served in the war, and is now in a hospital, a double amputee, standing for the thousands of Iraq veterans who have come home mutilated. The parts he was interested in still work, Mike tells her, with as little pity as Chigurh. In a reiteration of the same theme that does appear in the film, a soldier strangles his Doberman in the bathtub, only later to do the same thing to his terrified wife, who had appealed to the authorities, but was not taken seriously because the truths she conveyed were inconvenient.

At the end of “In The Valley Of Elah,” Hank hangs upside down the American flag his son had sent home from Iraq. Earlier, he had insisted that an upside down flag be righted, having explainer in a didactic yet important moment what the gesture means: “It’s an international distress signal…it means we are in a whole lot of trouble, so come save our ass, cause we haven’t got a prayer in hell of saving ourselves.”

What links these films to “Days Of Heaven” and to Cormac McCarthy’s masterpiece, “Blood Meridian,” is that they offer such similar commentaries on America’s history and identity. Near the end of “No Country For Old Men,” a slow elegiac dissolve brings Sheriff Bell to his uncle Ellis (Barry Corbin), an old-time law man. “I feel overmatched,” Bell says in his most important line, and one original to the film. Ellis offers no solace; there is nothing they can do to stop what the El Paso lawman (Rodger Boyce) called, on the occasion of Moss’s death, “the dismal tide.”

Ellis recounts how their Texas Ranger uncle Mac was “gunned down on his own porch” by a band of seven or eight me, “ahead of him,” as Chigurh throughout the film has always been a step ahead of Sheriff Bell. After a while, one of them “said something in Indian,” and then they rode off. (The Coens place this flashback in 1909, but McCarthy, with a wider historical appreciation, reflecting a sense of reprisal motivating Native Americans, chose 1879. McCarthy’s line, “one of em said something in injun,” remains).

“Days Of Heaven,” a masterpiece, and “No Country For Old Men” are the more accomplished works, avoiding the didacticism of “In The Valley Of Elah,” with the Coens’ film benefiting hugely from the distinction of its source novel. The absence of thematic explicitness allows Bill and Chigurh and Moss all to become paradigms for the American character rather than mere wayward individuals. Yet all three films ask implicitly the same question, one spoken in McCarthy’s novel: “How come people don’t feel like this country has got a lot to answer for.”

Vietnam and Iraq have become interchangeable, why “No Country” and “Valley of Elah” seems so similar thematically. In “No Country For Old Men” it is Vietnam that symbolizes the historical crime, so that in McCarthy’s novel, at the moment of his death, Carson Wells remembers suddenly, “the body of a child dead in a roadside ravine in another country.” The Iraq analogue is the photograph Paul Haggis intercuts several times: the corpse of a child in Iraq, run over by Mike and his comrades and then left abandoned by the side of a dusty road.

“What you’ve got ain’t nothing new,” Ellis says. The misery began with the settlers invading the continent. The stain of imperial domination, first at home at the moment of America’s creation, and later in Vietnam and Iraq, has borne an accelerating historical legacy symbolized by the spreading pool of Wells’s blood. Chigurh simply lifts his boots to avoid it. Anton Chigurh is America’s signature future, while Bell and his alter ego Hank Deerfield have found themselves no longer living in the country in which they were born.

Abrupt endings work best for these historical meditations on a country close to hitting moral bottom, a country where the highest officials have endorsed and approved of the use of torture. Linda disappears without a future. Sheriff Bell, now a broken, idle man, sits at his kitchen table, empty of occupation and usefulness to the community he had served since he was a twenty-five-year-old lawman. Defeated, he recounts his dreams to his wife, ending with the line, “And then I woke up,” which is also Cormac McCarthy’s final sentence.

So the Coens, and the novelist, urge us all to do.

This essay appeared in a slightly different version in “FILM QUARTERLY, Vol. 61, No. 3 (SPRING 2008). University of California Press.