buy stromectol in uk buy Lyrica Pregabalin Some Myths About MFA Programs And Other Reflections

By Joan Mellen

I didn’t anticipate a magical moment on that hot September afternoon, the first day of the fall semester when Temple University’s creative writing program inaugurated an MFA degree, replacing our old MA. There was a tangible alteration in the workshop atmosphere. Every head was held higher, every jaw set with determination. Where earlier those with purpose joined others with scant literary ambition, now a unified group of professional writers sat down at a seminar table to enter into a common enterprise.

Group solidarity grew geometrically. It emerged in workshop discussions and in the two page (or longer) written commentaries produced by each student for every story. These commentaries follow guidelines outlining the fictional strategies available, a clinic of the repertoire of techniques, an alphabet of craft. A workshop requirement is a rejection slip – or an acceptance letter – from a literary magazine. Now, during this first MFA semester, when students arrived with acceptance letters, spontaneous applause broke out, a measure of the energy and high spirits that accompanied the students’ seriousness of purpose.

George Saunders, among the most generous of writers, once offered a free workshop to Temple fiction students. In response to the inevitable question – how do you go about getting a story published? – Saunders produced a grid, an accountant’s ledger he had used in his early years to chart his short story submissions. Each entry was accompanied by the date on which the story was sent, the name of the magazine(s), and the date on which it was rejected. Their astonishment when George confessed that one story had garnered twenty-two rejections before being accepted by “The New Yorker” was palpable.

The best fiction workshop transcends genre. While workshop may be more manageable if students are restricted to distributing only short stories, it remains true that some are short story writers, but fare less well in a longer form (Alice Munro). Natural novelists are less successful with the short story (Michael Ondaatje). Some of my students distribute the first three chapters of a novel during the course of a semester, with the caveat that the later submissions will be compared with those earlier. All writing is story-telling, not least non-fiction.

When a student offers portions of a memoir, we examine the advantages of writing the piece as a novel, thereby transcending the exacting requirements of the memoir form. Among the basic lessons of any MFA program is that fiction writing involves no small amount of research: Recently we asked a workshop member for statistics in Japan pertaining to the number of Japanese who intermarry with Koreans.

At the heart of the workshop experience is the instructor’s conviction that every student can succeed and proceed to publication, a belief that you cannot fake. MFA programs are god’s work. They impress upon apprentice writers that hard work is the predicate of success, and an unassailable belief in yourself as a writer is the first premise. This core conviction has been embraced at Temple not only by the permanent faculty, but by the professional writing community, the international writers of renown who, for little money, have come to Philadelphia to spend a week with our students. Anita Desai’s largesse may be measured by the fact that she read a set of stories by our students, to whom she was offering one-on-one tutorials, not once but twice.

One year, the South African novelist, Andre Brink, arrived from Cape Town. When he praised one writer, another became visibly distressed. He was, she thought, remiss in not singling her writing out. I took this response not as hubris, but as a reflection of what all students should believe: that their work is worthy of serious notice. This young woman’s master’s thesis was published by a major trade publisher, and won a bushel of awards. True grit trumps talent with surprising frequency.

Another indispensable component of success for MFA writers is that they bring to their writing an authorial perspective, a set of convictions suffusing their narratives and the views of their characters, and that these convictions permeate the work. Our MFA students are required to take several literature courses offered by the Ph.D. program. Among those is “Poetics of the Novel.”

What is crucial for creative writing students is the realization that embedded in the texture of successful novels lie the author’s strong personal convictions. This is true of Dostoevsky in “The Possessed,” as he warns against the nihilism that presaged inevitable societal transformation. It is no less true of Stendhal in “The Charterhouse of Parma.” Stendhal taught future novelists, Tolstoy among them, that characters live and dream in history. Moral indignation at the injustices of his society pervades Cervantes’ “Don Quixote,” the novel with which “Poetics of the Novel” begins.

In an effort to encourage our students to identify their own convictions, on the first day of workshop I present the students with a quotation from a published novel or story (author unknown). Within a half hour they must write a complete short story deploying that quotation as its first sentence. Once I chose lines from Franz Kafka: “You can hold back from the suffering of the world. You have free permission to do so, and it is in accordance with your nature. But perhaps this very holding back is the one suffering you could have avoided.”

For another semester, I chose the epigraph from Don DeLillo’s “Libra”: “Happiness is not based on oneself, it does not consist of a small home, of taking and getting. Happiness is taking part in the struggle, where there is no borderline between one’s own personal world, and the world in general.”

The author of those lines was not DeLillo, but Lee Harvey Oswald, in a letter to his brother. At the end of semester class party, the students chipped in and brought, with mysterious smiles, a butter cream layer cake. Inscribed on top was a paraphrase of Oswald’s earnest words: “Happiness is the Struggle.”

Our fiction workshops are accompanied by craft courses. I give one on setting. The students are assigned to write novellas, situating their action in the history of the moment at which the story unfolds. Setting rivals character as the piece’s focal point; among the books we read are Faulkner’s “The Bear,” Garcia Marquez’s “Chronicle Of A Death Foretold,” and Haruki Murakami’s “The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle.”

The myth that MFA programs are hotbeds of jealousy and back-biting exemplifies what students call an “urban legend.” Should it happen, and on rare occasions it does, that the class withholds praise from a work of genuine accomplishment, the instructor is there to right the ship. The MFA classroom functions most of the time as a safe place, an arena to challenge received wisdom. I often assign a 1987 “New York Times” essay by William Gass, “A Failing Grade For The Present Tense.” We ignore its anachronistic attack on MFA programs, and its careless dismissal of “R. Carver.” What’s important is that the choice to write in the present tense should not be reflexive, but considered and selected for its thematic resonance.

This past semester several workshop members – Carver fans all – were eager to examine the role of Gordon Lish in Carver’s publishing career. The results reinforced a welcome truism: a vital workshop is student directed. A student enrolled in both “Poetics of the Novel” and a fiction workshop invoked what he had learned from Stendhal. The MFA writers are among those singled out by Stendhal on the final page of “The Charterhouse of Parma,” part of a “happy few.”

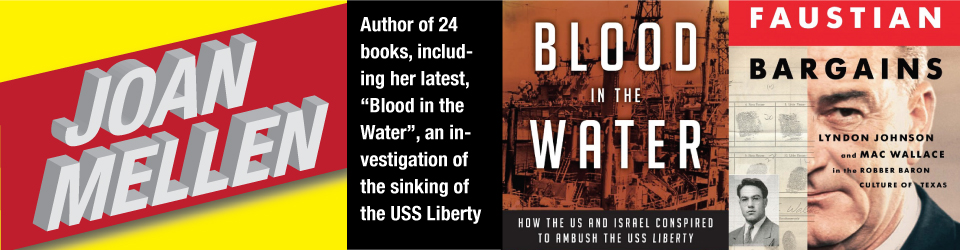

Joan Mellen (joanmellen@aol.com) is a professor in the graduate program in creative writing at Temple University in Philadelphia. She is the author of twenty books, including the novel “Natural Tendencies,” biographies of Lillian Hellman, Dashiell Hammett, Kay Boyle, and basketball coach Bob Knight, multiple works on the art of cinema, and an investigation into the Kennedy assassination, “A Farewell To Justice.”