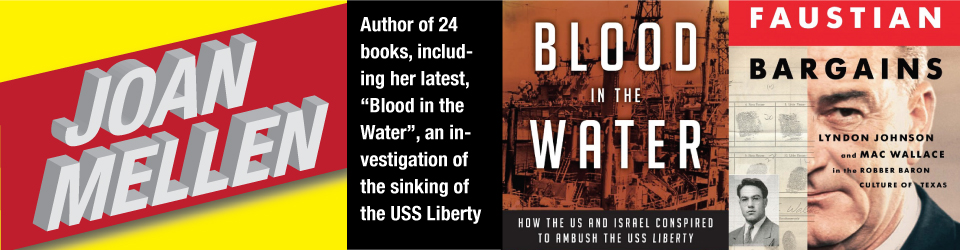

JOAN MELLEN BOOKS & BOOKS PRESENTATION

March 13, 2013

“The Great Game In Cuba: How The CIA Sabotaged Its Own Plot To Unseat Fidel Castro

Thank you very much for coming to this talk about “The Great Game In Cuba.” The title is a British locution referring to the intelligence services, in particular, MI6. My book is about CIA’s treatment of the Cuban struggle to unseat Fidel Castro. What I learned surprised me although it may not surprise people here tonight.

Given the 1967 CIA Inspector General’s Report of CIA-Mafia plots to assassinate Fidel Castro, we might have supposed that CIA would support the anti-Castro militants determined to conduct their struggle inside Cuba. Yet this was far from the case. In reality, CIA opposed and sabotaged those efforts. My book looks into CIA motives and methods and tells a story that hasn’t been told before, at least by an American.

My primary sources are unsung heroes, first Alberto Fernandez, “the man of the boats,” who, alas, died last October, and Gustavo de los Reyes, who at the age of 99, is here tonight, having lived to tell the tale after being imprisoned at La Cabana prison and then for four years on the Isle of Pines.

I have never been to Cuba and I have a feeling that there are people here who are very knowledgeable about these subjects and from whom I can learn a great deal. Please feel free to comment in our question period.

My original idea was to write about the close relationship between certain Texans like Herman & George Brown of Brown & Root and CIA. Among those Texans was the “cowboy” who appears on the cover of The Great Game In Cuba. This is no ordinary cowboy: it is Robert J. Kleberg, Jr., President of King Ranch, the largest in the United States. With its nine satellite ranches, King Ranch would grow to be the largest in the world.

Closest to Kleberg’s heart among those ranches was Becerra in Camaguey Province, Cuba. About Kleberg, I want to say first this: his passion was cattle, and he was the first person in the western hemisphere through genetic breeding to create an entirely new species, which he named after the original land grant of King Ranch, Santa Gertrudis.

Kleberg ran King Ranch from the time he was 21 years old, until his death at 78. When his grandmother died, and he lacked the cash to pay the inheritance taxes, he leased King Ranch to a company called Humble Oil, later EXXON. For six years, only dry wells resulted. Then, in 1939 the oil came in and never stopped.

Instead of paying dividends to his relatives, who were co-owners of King Ranch, Kleberg invested the money in satellite King Ranches. Money was not his motive. It might sound grandiose, but it was true: Kleberg believed that his purpose was to help feed the world’s hungry. The portrait of Kleberg concocted by the writer Edna Ferber in her pot-boiler, “Giant,” as a racist and a snob is entirely inaccurate, and was based on revenge. Kleberg didn’t like this “lady writer” and made no secret of it when she visited King Ranch in another of my favorite scenes in the book.

Kleberg never took any money out of Cuba during the 1950’s when he was building Becerra; and he paid his Cuban workers so well that when Castro came to power, Kleberg’s foreman Lowell Tash had no fear that they would turn against him. Kleberg’s hope was that Cuba would become a source of beef – for the United States.

Managing the ranch in Cuba for Kleberg was another figure also less known to history than he should be: Michael J. P. Malone. Malone was a vice-president of the Czarnikow-Rionda sugar brokerage based on Wall Street in New York. He had served earlier as the chief aide of the Archbishop of New York, Francis, Cardinal Spellman, and was a man so close to CIA that he had at least five CIA handlers. Malone was also close to J. Edgar Hoover and to Frank O’Brien at the New York field office of the FBI, who rented a house on Key Biscayne. Malone is the James Bond of this story as he spirits people out of Fidel Castro’s prisons.

I enjoyed the moment when Malone and Kleberg met for the first time at King Ranch in Texas in 1950. Kleberg, who was a good judge of human beings, as of horse flesh, at once told Malone, “You are the new president.” He would run Compania Ganadera Becerra in Camaguey province.

“I know nothing about cattle,” Jack Malone said.

“I’ll take care of the cattle,” Kleberg said. “You take care of everything else.” That “everything else” would include a good deal of international intrigue.

In my book, Alberto Fernandez calls Kleberg “Uncle.” Through Malone, Kleberg offered financial and other help to Fernandez as he began his work through the group “Unidad Revolucionaria.” After Castro took power, Alberto ran the sugar industry for one crop, and it was during that season, beginning in January 1959, that he made contact with Humberto Sori Marin, whose story is also told in “The Great Game In Cuba,” to the degree that I was able to tell it. My chief source was Alberto Fernandez, with whom I spoke in Key Biscayne over a three year period.

The scene I depict of how Camilo Cienfuegos died was told to me by Alberto Fernandez, as told to him by Humberto Sori Marin. I placed it in italics because it is hearsay. The cliché that reporters should have two sources before stating anything is profoundly unrealistic. We’re lucky to find one source for an event that was concealed so successfully from the historical record as this one has been.

Camilo’s biographer, Carlos Franqui, admitted in his book that he was not satisfied with the explanation that Camilo’s plane somehow vanished at sea. There was no wreckage, the weather was fine, and he was not traveling out at sea but from Camaguey to Havana. The manager of the tiny Camaguey airport who called the rescue effort perfunctory at best, was found two weeks later with a bullet in his brain. His death was ruled a suicide. Maybe some people here have heard the story of what happened behind palace walls; I’d be grateful to know that. The fact I discovered was that Fidel Castro shot his comrade Camilo Cienfuegos.

Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. was a close friend both of the director of central intelligence, Allen Dulles, and J. Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI. Kleberg assumed that the State Department and these agencies would assist in returning Becerra to him after it was confiscated by INRA. This would not be the case. Most of the people in this story were astonished at CIA’s indifference to their survival.

The first surprise belonged to Humberto Sori Marin, whom Alberto exfiltrated from Cuba on March 1, 1961, on his ship, the Tejana after several unsuccessful attempts (One of the photographs on the cover is of Sori and Alberto on the submarine chaser). I should add that in the month of March 1961 Alberto infiltrated 19,000 pounds of ammunition into Cuba. Only 12,700 pounds had been infiltrated during the previous six months by all other boats combined.

Sori’s aim was to meet with CIA to discuss the logistics of the coming invasion of Cuba, in particular the location of the landing. Sori brought with him a “Plan” which I include in the book (after p. 144) in its original Spanish version).

Sori met with CIA and returned to Cuba believing that CIA had abandoned the location at the Zapata peninsula, which many knew was a choice that ensured defeat. I quote a CIA asset, Edward Browder, who remarked, “It was common street knowledge that the [Bay of Pigs] operation was to occur and that it would fail…the CIA deliberately botched the operation.”

At a meeting of President Kennedy’s Special group on the subject of the invasion, the guerrilla warfare expert, Colonel Edward Lansdale, could not remain silent: “We’re going to get clobbered!” he said. Before he could utter another word, Allen Dulles cut him off.

“You’re not a principal in this!” Dulles told him. Later Dulles ordered Lansdale to keep his mouth shut, “as a favor for past efforts.”

By July 1961, it was clear. Tony Varona complained to the State Department that the United States “was abandoning Cuba to its fate under Castro.” Arthur Schlesinger said the same thing: “Those most capable of rallying popular support against the Castro regime are going to be more independent, more principled and perhaps more radical than the compliant and manageable types which CIA would prefer for its operational purposes.” He might have been describing Alberto Fernandez.

I tell the story of Sori’s capture, not as former Castro security chief Fabian Escalante tells it in his self-aggrandizing book, called The Secret War, but as Alberto Fernandez explained it to me. It’s a heartbreaking story. Sori’s capture and subsequent execution were not the result of superior Cuban intelligence and surveillance of Sori.

I have two trenchant examples of CIA’s betrayals of its pretended Cuban friends in the book. The first concerns the Cuban rancher and agronomist, Gustavo de los Reyes. It took place before the Castro government confiscated his property. Along with a group of oppositionists, Mr. De Los Reyes joined a plot of cattlemen who had formed a group with the goal of building a popular movement to oust Castro. It seemed appropriate that the group inform CIA of its intentions. In the company of Michael J. P. Malone, and George A. Braga, the head of Czarnikow-Rionda, on or about August 1, 1959, de los Reyes flew to Washington. There Allen Dulles received the group.

Dulles immediately took the offensive.

“We don’t agree with what your group is doing,” Dulles said. “We’re on good terms with Russia. Castro is their ally. We don’t want trouble with Russia and so we can’t back efforts against Castro.” Then Dulles added, “Morgan is a crook!” This was William Morgan, a former U.S. Marine and CIA asset, who had joined the plot.

Dulles followed this diatribe with a seeming non sequitor.

“How much money do you need?”

“We don’t need any money,” de los Reyes said. “We’re here to notify you of our intentions.”

When de los Reyes refused CIA’s money, the meeting was over. If you wanted CIA’s help, you had to demonstrate your good faith by accepting their cash. You had to accept their domination. They would control your efforts. You would follow their policies.

“We cannot back you,” Dulles said. “If you don’t put a stop to this, you’ll end up in a Cuban jail – or a cemetery.”

“I’d prefer the cemetery to doing nothing,” de los Reyes said. As he was departing, he asked Dulles to keep the meeting confidential since lives, including his own, were at stake.

Ignoring this caution, Dulles immediately contacted the State Department, telling Ambassador Philip Bonsal everything. Bonsal then sent a telegram to Cuban foreign minister Raul Roa. It wasn’t long before the cattlemen found themselves in the horrific La Cabana prison facing what seemed to be certain execution. The photograph on the cover of The Great Game In Cuba is of the attorney representing Gustavo de los Reyes pointing his finger in Fidel Castro’s face and demanding that de los Reyes’ name be removed from the list of those facing execution.

“If I save one, I have to save all,” Castro said, refusing his plea. I hope you will read the rest of the story in the book.

Alberto Fernandez did not work under CIA domination either, although he believed that he would not be able to operate without CIA help. CIA, who named him AMDENIM-1, was suspicious of Alberto from the start. The Agency didn’t like his simplicity. They were wary of his lack of interest in renewing the privileged style of life that he had enjoyed as a rich man in Cuba. They noted his “shrewdness.” They did not much like that he spoke English so well, the consequence of his having attended Choate, where one of his classmates and acquaintances was John F. Kennedy, as well as Princeton University.

Alberto had already outfitted the Tejana for forays into Cuba when CIA made its presence felt. Alberto had first operated two smaller vessels. One he named for his three children, the ILMAFE, a twenty-two footer. The next was a Chris Craft called El Real. Then he bought the Tejana, a 116 foot submarine chaser that had engaged with German submarines during World War II. Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. gave him $38,000; the rest of the money, about the same amount, he supplied himself.

When they sailed into Cuban waters, the captain was Armando Rodriguez Alonso, who had been an officer in the Cuban navy. In American waters, they used a long-time CIA asset named Lawrence Laborde, whom Alberto called a “Louisiana bayou pirate.”

CIA let Alberto know that the Agency was contributing several crates of weapons to its inaugural effort. Alberto hesitated before loading these crates onto the ship.

“Let’s see what we’re taking in,” he said. He and Armando decided to open a few packages.

Uncovering the weatherproofing, Alberto discovered boxes of old Springfield rifles, dating from 1903.They were of the vintage used by General Pershing in his battles with Pancho Villa. The actions of these rifles were so decrepit that they rattled when you shook them. If the weapons dated from World War I, or earlier, Alberto concluded, CIA could claim deniability. They could argue that such weapons could not possibly have originated with the Agency. Other people, like Martin Xavier Casey, had a similar experience with CIA’s gifts of weapons.

In the crates with the Springfield rifles, Alberto found bags full of a religious manifesto by a Catholic bishop called Eduardo Boza Masvidal. What would the members of Unidad’s underground in Cuba have thought if Alberto had brought them not only those useless weapons, but the Bishop’s irrelevant manifesto? Alberto thought. Alberto dumped the religious pamphlets into the ocean. Then he telephoned CIA’s munitions warehouse.

“When you decide to be decent people,” he said. “Let me hear from you.” Another Cuban militant who had a similar experience and whose story is told in my book is Dionisio Pastrana, now the chief of Goodwill Industries of South Florida. Dionisio, a very young man then, was shocked to discover that CIA forbade the Cubans in their joint operations from carrying the most advanced U.S.-manufactured automatic weapons. Instead, they were given older models or weapons CIA purchased from foreign countries. One was an extremely heavy M-3 submachine gun. The 65-pound radio was powered by a very heavy generator.

Still, Dionisio succeeded in all his missions, confirming that Soviet tactical missiles remained in Cuba after the missile crisis under the discretion of local commanders. He also brought back fragments of the Soviet missile that had shot down the American U-2, revealing the quality and level of the steel the Soviets were producing for their supersonic weapons. His CIA handler, Bob Wall, congratulated him for having contributed to Israel’s 1967 seven days war.

What emerges from my narrative is a glimpse into CIA’s motives, its duplicitous methods. It became clear to Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. that CIA policy did not include an effort to unseat Fidel Castro. U.S. and CIA interests lay in a protracted war, one that they succeeded in supporting in Southeast Asia. What they wanted was a war of duration: victory was about keeping the war going as long as possible so that greater profits could accrue to the Agency’s defense contractor allies, like Brown & Root.

CIA’s first concern was itself as an institution, justifying its unlimited budget. The Agency opposed anyone who did not follow CIA agendas and policies. The Cubans who fared best during these years submitted to the Agency’s demand that they join the Agency-created Cuban Revolutionary Council. This Alberto Fernandez would never do.

I also included some unique scenes, taken from CIA documents released under the JFK Act, although they have nothing to do with the Kennedy assassination. These reveal that although CIA officers had been elected to no office, they were making policy for the United States, in defiance of the president and congress. Michael J. P. Malone, I show, conferred regularly with CIA’s David Atlee Phillips, whom he gave a code name: Phillips was his “Chivas Regal Friend.” Malone, Kleberg, and Phillips, along with a high-ranking Western Hemisphere officer named Radford Herbert, discussed which Latin American countries deserved loans from the United States, and which did not. Colombia and Argentina were high on their list. Chile was low and was to be refused loans because they had voted against the U.S. at Punta del Este.

These men referred to John F. Kennedy as if he were a child. His nickname was “Little Boy Blue.” JFK was “soft” and naïve. Bobby Kennedy they termed “a strong-minded individual and if he made a decision would carry it out.” Chivas Regal and Radford Herbert both advised Malone and Kleberg to work on Bobby.

Kleberg also funded CIA’s front for labor in Latin America (“The American Institute For Free Labor Development”) and opposed the Alliance for Progress. Malone met with Robert Kennedy and was pleased to learn that he planned to persuade his brother, the president, to fire Arthur Schlesinger. In 1960, Kleberg also contributed money to a plot to assassinate Fidel Castro, where he joined with a Mr. Lykes of Lykes Steamship Company and a United Fruit Company representative. Their idea was to assassinate Fidel and Raul Castro, also Che Guevara, and then take over the Cuban Government and place at its head one Francisco Caneas. The MEMORANDUM FOR THE RECORD describing this plan is titled: Cuban Revolutionary Activity in Florida and is dated 15 January 1960.

Some CIA operatives felt sorry for Alberto Fernandez, whom they called “basically a very soft-hearted guy.” They noted that had he not given away so much money to his former sugar institute and ranch employees, he could have postponed his own financial problems. CIA called Alberto “basically a sentimentalist.”

Robert J. Kleberg, Jr. did not abandon his Cuban friends. When after four years on the Isle of Pines, Gustavo de los Reyes found an opportunity to return to the United States, Kleberg provided him with the opportunity to run a King ranch in Venezuela. Before he went to Venezuela, de los Reyes tried to place an article discussing his experience in Cuban prisons in Reader’s Digest magazine with the assistance of Michael J. P. Malone.

CIA played a major role in censoring the article. That censorship included their cutting the story of de los Reyes’ meeting with Allen Dulles. It’s clear that Reader’s Digest was a CIA-controlled magazine. “We’re asking you to cut some things because they’re detrimental to the prestige of the United States,” the CIA agent said.

“The detrimental thing is not to tell the truth,” a furious de los Reyes said. “I’m in a free country.” Not quite. Not even Kleberg could make CIA back down.

My favorite story that Mr. de los Reyes told me about him and his close friend Kleberg was about a book. Kleberg was not an intellectual and his favorite reading was cowboy novels. One day de los Reyes presented him with a copy of Machiavelli’s The Prince.

“This man is a son-of-a-bitch,” Kleberg said when he was done.

“I gave it to you to defend yourself,” de los Reyes said. “To warn you to be cautious with man.”

“I already know that,” Kleberg said. “I thought you wanted me to imitate him!”

Kleberg offered Alberto Fernandez a similar opportunity to revive his finances. Kleberg flew to Bal Harbor to have dinner with Alberto. “I appreciate Alberto’s commitment to rid Cuba of Fidel Castro,” he said. But it was not meant to be. He thought he might buy land on the Amazon, on the Mato Grosso, where he could create a steer-feeding operation. He would buy that forest only if Alberto agreed to be in charge.

“I can’t give this up, I can’t leave this,” Alberto said, as he declined Kleberg’s offer. For him, the struggle was not yet over, nor would it ever be. They were never to meet again.

In The Great Game In Cuba, I tried to introduce some important figures who have passed beneath the radar of history. In part, this was because they preferred it that way: Robert J. Kleberg, Jr.; Michael J. P. Malone; Alberto Fernandez; Gustavo de los Reyes; Dionisio Pastrana have in common that they sought neither fame nor glory. These were people of convictions and purpose and they were not in search of money or notoriety. Kleberg never took any money out of his Cuban operation. He had to live with the fact that the Santa Gertrudis animals he had sent to Cuba wound up in the Soviet Union as part of Fidel Castro’s Faustian bargain with the Soviets.

Kleberg operated as a world leader without portfolio not least when he put King Ranch resources at the service of the liberation of Cuba. For all these people, their values were their calling card. Although Allen Dulles flew to King Ranch to ask for Kleberg’s advice right after he became Director of Central Intelligence in 1953, the issue was always what the Agency could do to further the causes in which Kleberg believed, never the other way around.

When CIA disappointed him, and Alberto Fernandez, Kleberg does not seem to have been surprised. Kleberg knew all about hired hands, whether they were named “Lyndon Johnson,” “Allen Dulles” or “J. Edgar Hoover.”

Kleberg amazed George Braga when they met in Cuba and all Kleberg wanted to talk about was – grass. “Grass is the forgiveness of nature,” he said, “her constant benediction…forests decay, harvests perish, flowers vanish but grass is immortal. Should its harvest fail for a single year, famine would depopulate the world.”

I wrote a book about good people who, I believe, deserve our attention not least now, all these long years later.