Good morning. My name is Joan Mellen, and I’ve come to this conference commemorating Oliver Stone and his film “JFK” wearing three hats:

- As a student and teacher of film studies

- As a writer about the Kennedy assassination

- And as the biographer of Jim Garrison

Many in this room could recite a litany of films that have played a role in illuminating history while advocating social change: “The Grand Illusion,” “All Quiet On the Western Front,” “Gentleman’s Agreement,” Oliver Stone’s own “Platoon” and “Born On The Fourth of July.” But “JFK” is different: “JFK” became an ACT of history.

From revealing the truth about the Kennedy assassination, and “JFK” does that, accurately, despite CIA’s efforts to say otherwise, Oliver Stone’s film went on to become a historical event in its own right. Stone’s film restored interest in the Kennedy assassination to new generations, people born too late to be susceptible to the obfuscations of the Warren Report and the confused Report of the House Select Committee On Assassinations with its emphasis on the Mafia. That we know.

What “JFK” did that is even more remarkable was to make possible the revelation of truths behind American power that had previously been concealed from the public. Oliver Stone’s “JFK” revolutionized the writing of American history of the second half of the twentieth century.

When “JFK” appeared, it had been almost thirty years since the publication of the Warren Report, and fifteen years after the obscurities produced by the House Select Committee on Assassinations. JFK awakened so profound a response that people demanded to know from the government what happened to the president. The outcry was so determined that it inspired Congress to pass the John F. Kennedy Assassination Records Collection Act of 1992.

More than five million documents flooded the National Archives. They issued largely from CIA and the FBI, and led to an exposure of the role of the intelligence services in the exercise of American power. There were also documents from military intelligence, teaching us that in the chain of power, the military took second place to intelligence. Some records issued from U. S. Customs and from the Office of Naval Intelligence. There were even documents from the Internal Revenue Service.

None of the histories of the Kennedy assassination published in the past twenty years could have been written without the documents made available under the JFK Act, although the writers have not chosen to acknowledge either Jim Garrison or Oliver Stone. Shame on them.

The releases kept coming into the millennium and ground to a halt finally under the repressive Obama government when transparency has become a distant memory. What most interested me about this process was that although the law was named John F. Kennedy Records Collection Act, in reality the documents now residing at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland far transcend the events of November 22, 1963 and their aftermath. They chronicle the exercise of American foreign policy and history far beyond the JFK assassination.

I’d like to offer some examples of the scope and breadth of the documents that became available thanks to the public reaction to Oliver Stone’s film. One document I utilized in my book “The Great Game In Cuba,” which is not about the Kennedy assassination, depicts the right hand man of the CEO of King Ranch in Texas, the largest ranch in the U.S., whose name was Michael J. P. Malone. There are documents depicting how Malone and CIA officer David Atlee Phillips, whose name is a footprint in JFK assassination research, created U.S. foreign policy in minute detail.

Michael J. P. Malone is not a name known to history: both he and his boss Robert J. Kleberg, Jr., preferred it that way. Prior to his becoming the manager of King Ranch in Cuba, Malone had been a vice-president of the Czarnikow-Rionda sugar brokerage, and before that had been chief aide to the Archbishop of New York, Francis, Cardinal Spellman.

Malone was so highly connected in CIA that he was in touch with five CIA officers. In a memo released under the JFK Act, Malone and Phillips mull over to which Latin American presidents the U.S. ought to extend loans and which should be excluded. Malone called Phillips “Dave” to his face and his “Chivas Regal friend” when he wanted to use code.

So we learn, as a result of a film depicting the murder of the president, how in the year 1962 foreign policy was fashioned by CIA, on behalf of the corporations it served. We observe CIA officers working with the leader of a corporation without any advice or consent from a president or a congress, or any elected official. This is direct evidence, and we would not have it were it not for a film director named Oliver Stone. Behind Stone of course is the figure who inspired him, the much abused district attorney of Orleans Parish, Louisiana, Jim Garrison.

No writer can explore with any accuracy the role of the intelligence services in American society without consulting the documents released under the JFK Act. This is the astonishing historical achievement of the film “JFK.”

I could not have written my last three books, “A Farewell to Justice,” which is a study of Jim Garrison’s investigation; “Our Man In Haiti” about George de Mohrenschildt; and “The Great Game In Cuba” were it not for the JFK Act documents.

My biography of Jim Garrison and his investigation, was published in 2005, and reissued this past September. It explores Jim Garrison’s investigation from the perspective of the documents released after his death in 1992. Garrison in 1967 concluded that the man he charged with participation in the murder of President Kennedy, Clay Shaw (played in the film by Tommy Lee Jones) was working for the Central Intelligence Agency at the time that Shaw traveled around the state of Louisiana in the company of Lee Harvey Oswald and a CIA contract pilot named David Ferrie.

Thanks to the JFK Act, CIA obliged us in 1992 with a document issuing from its History Review Group’s project files that proves that Garrison was correct in his assessment of Shaw. It states clearly and unequivocally that Clay Shaw “was a highly paid CIA contract source”. CIA adds “until 1956,” but research has revealed that many of CIA’s end dates for service to the Agency are inaccurate.

William Gaudet, who edited “Latin American Reports” out of Clay Shaw’s International Trade Mart, laughed when he saw that CIA provided end dates for him on documents. He declared there never WAS an end date, he never ceased to be an Agency asset.

Another CIA document lists the end date of Herman Brown’s employment by the clandestine services as 1966 – which was four years after Herman’s death in 1962.

Thanks to Oliver Stone, the curtain lifts on the relationship between CIA’s multifarious components. We discover the degree to which CIA has engaged in policy making. We have evidence that CIA has overridden the wishes of mere Presidents from the moment it came into existence in 1947.

To assess the contribution Oliver Stone’s film has made to our historical understanding, I’d like to explore with you just a few more of those more than five million documents released under the auspices of the JFK Act.

I was able to write a book about Haiti during the time of Papa Doc, Francois Duvalier, with the help of records of the 902nd Military Intelligence Group because these documents sit in the John F. Kennedy records collection. They reveal how a Haitian banker named Clemard Joseph Charles conspired with CIA to overthrow the President of Haiti, Francois Duvalier, and to place Charles himself in the Presidency.

The documents present a portrait of a Haiti overridden with scoundrels, and rascals, and soldiers of fortune. They expose the U.S. role in protecting the interests of American corporations in Haiti, a role confirmed by the wikileaks cables provided by Private Manning.

In my 2013 book about Cuba, I expose the ambiguity of CIA’s ostensible efforts to help Cubans overthrow Castro. The documents reveal that CIA’s interests were entirely in itself as an institution, its power, its unlimited finances and its control over those it seemed to be assisting. Like those connected to Haiti, these records, having nothing to do with the Kennedy assassination, expose the process by which CIA, suddenly and abruptly, moved U.S. efforts away from Cuba and to Southeast Asia.

We learn about the architecture of the Vietnam War from the CIA documents of those years. We discover the specifics of the relationship between Texas defense contractors and the Agency. Were it not for the JFK Act, I would not have a CIA document stating that both Herman and George Brown, proprietors of Brown & Root, had been assets of CIA’s clandestine services from the early 1950’s on.

CIA had also enlisted a slew of Brown & Root executives. Here we have the heads of major corporations enjoying a symbiotic relationship with the intelligence services. We watch Brown & Root, which became a Halliburton subsidiary in 1962, functioning as part of the U.S. military, assisted by the U.S. Navy.

That document outlining Brown & Root’s relationship with CIA issued from the all-powerful Office of Security, which shared Herman and George Brown as assets with the clandestine services. The JFK Act has taught us a great deal about the internal structure of CIA, and the rivalries within, details we would never have penetrated were it not for the extraordinary public response to Oliver Stone’s film.

From the documents, we learn that CIA uses and has used a significant number of corporations for cover for its people. When H. L. Hunt and Nelson Bunker Hunt, as I show in a long addendum about the Hunts in my book about Haiti, refused to allow CIA access to their operations, particularly in Libya, CIA sent an asset named Paul Rothermel to infiltrate Hunt Oil and to cast suspicion on old man Hunt as a principal in the Kennedy assassination, which he was not. CIA had no trouble finding a major corporation to host its assets in Libya: long-time CIA ally, Bechtel, was more than happy to oblige.

Meaningful histories of the Vietnam era cannot be written without the JFK Act documents, whether or not the authors award Oliver Stone the credit he deserves.

We would not know how extensively CIA has over the years monitored our mail had CIA files not outlined the Agency’s opening the mail of George de Mohrenschildt when he lived in Haiti, beginning in May 1963. CIA then ordered the FBI to conduct an investigation of every person who wrote to de Mohrenschildt. We would not know how CIA used its media assets if we did not have an April 4, 1967 document directing these assets on how to answer critics of the Warren Report, by whom they meant the person who was eviscerating the Warren Report at the time, Jim Garrison.

From the Church committee testimonies – those that CIA has consented to release – we learn that CIA placed its officers in both the Republican and Democratic National Committees. This was revealed by long-time CIA General Counsel, Lawrence Houston. CIA at least knew that there was no substantive difference between Democrats and Republicans.

From James Angleton, long time head of counter intelligence, we learn that “dissembling,” a favorite CIA word, has been the norm among many CIA officers; so Angleton declared before the Church committee that CIA did not debrief Lee Harvey Oswald upon his return from the Soviet Union. The documentary evidence suggests otherwise. From Church committee summaries of testimonies that remain secret, we learn that Lee Harvey Oswald was often seen in the company of officers of U.S. Custom and the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

One INS (Immigration and Naturalization) Officer, Wendell G. Roache, told the Church Committee that he had been waiting for twelve years for someone to ask him about Oswald. Were it not for Jim Garrison, there would have been no Church Committee and were it not for Oliver Stone we would not have access to those testimonies that have been released to the National Archives. The comment from Wendell G. Roache about waiting for twelve years appears in the committee’s summary of David Smith’s testimony. Perhaps those testimonies will finally be released in 2017, perhaps not ever. But we know that they exist, and that Customs had some relationship with Lee Oswald in New Orleans.

The records have Allen Dulles lying in suggesting that the landing for the Bay of Pigs invasion was chosen by the U.S. military. If we peruse these records we discover that the military was lower on the chain of power than CIA, that the military provided cover – including lifetime cover – for CIA employees.

We learn that on occasion Allen Dulles intervened when it came to promotions for CIA’s favorite agents working under military cover. One striking example was Edward Lansdale, who became a general on the urging of – Allen Dulles. The Pentagon did not want to promote Lansdale…Dulles intervened and twisted its arm.

General Lansdale makes an appearance in the film “JFK”, and I remember thinking when I first “JFK,” too bad Oliver Stone spoiled the film by placing Colonel Edward Lansdale at the scene of the Kennedy assassination.

Then I discovered General Victor Krulak’s letter to Fletcher Prouty of 15 March 1985. Krulak had worked alongside Lansdale at the Pentagon (Lansdale was CIA under military cover for his entire career), and knew Lansdale well. Having viewed a photograph taken at Dealey Plaza on November 22nd, General Krulak says in a letter to his Pentagon colleague, Fletcher Prouty, “The haircut, the stoop, the twisted left hand, the large class ring. It’s Lansdale. What in the world was he doing there?” (Prouty was chief was special operations within the Pentagon; he worked under General Erskine).

I was delighted to have Victor Krulak’s letter, and to add further truth to the larger truths of “JFK.” The letter resided in Fletcher Prouty’s papers and was made available by Len Osanic, the archivist of the Prouty papers.

Don’t underestimate Oliver Stone’s research team that worked on “JFK.” The film is overwhelmingly accurate, no matter that Thomas Edward Beckham, a substitute patsy pretended to another identity when Oliver Stone’s researcher finally located him, and no matter that there are composites because some Garrison witnesses did not want their names used.

Another enlightening truth among the documents released under the JFK Act is contained in a 1975 CIA document that reads, “The NYT (New York Times) computer can be monitored.” This document issued from Counter Intelligence’s Research & Analysis Branch.” CIA has long enjoyed the ability to hack into the New York Times’ computers. This was nearly 40 years before Edward Snowden’s NSA revelations.

Thanks to the JFK Act, we have CIA officer Seymour Halpern’s interview with CIA’s history component, the internal History Review Group, revealing the part Robert Kennedy played in assassination attempts on the life of Fidel Castro. Halpern’s perplexity – wasn’t Bobby an opponent of the Mafia, why then was he recruiting Mafia figures to kill Fidel Castro? – suggests an answer to Jim Garrison’s own questions when faced by Bobby’s attempts to obstruct his investigation. Garrison in 1967 could not understand the inner workings of CIA, but thanks to Oliver Stone’s work, we are learning who runs this country, and where the decision-making process really lies.

It took enormous courage on Oliver Stone’s part to make a film about Jim Garrison. When the attacks came, and they came heavy and early, long before the film was released, and have not yet subsided, as most people in this room know, Stone called the publisher of Garrison’s book, On The Trail Of The Assassins, and said, tongue in cheek, “why didn’t you tell me so many people hated Jim Garrison?” That’s an understatement. Perhaps the most powerful institution in American society had set its sights on destroying Jim Garrison.

About “JFK” itself: I’d like to suggest that among its other achievements is that this film firmly and forever breaks down the barrier between fiction and non-fiction films: what is documentary and what is a dramatic film? This is a good thing, since it has long been a truism that documentaries cannot claim to an absolute truth in any meaningful way.

Truth is embroidered throughout JFK. At times it soars to the heights of documentary. At others, it posits a dreamy fiction, Garrison’s happy family life as it never was, but as it might have been.

The whole, a felicitous blending of genres, exposes truths of the Kennedy assassination that had hitherto been suppressed or ignored or not yet excavated. On the level of art, everything is true, and a composite may be truer than a literal-minded journalistic depiction of an actual witness.

A once and future CIA contact acquaintance of mine said that the part of JFK he enjoyed most was Garrison’s dialogue with Mr. X, played by Donald Sutherland, which never happened in real time; the endorsement by this person told me that the truths of that scene were spot on. He worked closely with David Atlee Phillips, that highly-placed CIA officer close to the events of the Kennedy assassination. He told me how much David Phillips hated John F. Kennedy.

This man confirmed for me what Mr. X says in the film, that “CIA let the assassination happen.” General Y, to whom Mr. X refers, is of course Edward Lansdale.

Oliver Stone confirmed Jim Garrison’s thesis that the footprint of CIA was everywhere that Lee Oswald walked. “JFK” has to its credit the passage of the JFK Act that yielded a flood of documents. These in turn have pointed to certain elements of the Agency being involved in the murder of President Kennedy.

This conference today for me represents an homage to Oliver Stone, who risked his career to seek and tell the truth about the Kennedy assassination as Jim Garrison discovered it. As I told him last week in Pittsburgh at the Wecht conference, practically in tears, we all owe him an enormous debt of gratitude. When I interviewed Stone for “A Farewell To Justice,” I asked him whether Warner Brothers had requested that he make any cuts. He said, wistfully, “I was a hot director then.”

What resulted in “JFK” was an expose of the workings of American power in minute detail. Mainstream historians have not yet granted to Oliver Stone credit for his remarkable achievement. Film critics seem to prefer such evasive works as “The Hurt Locker.”

It is time that Oliver Stone be applauded for this astonishing movie, that became so much more than a movie.

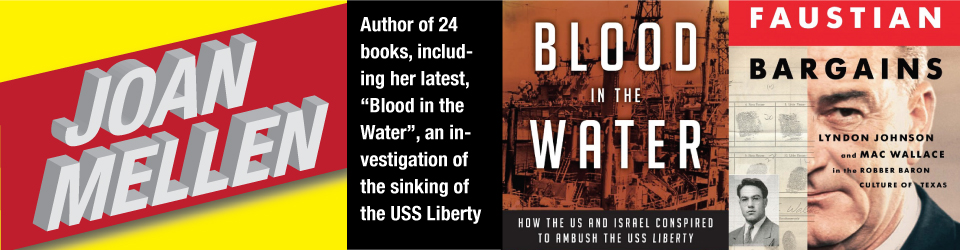

Joan Mellen